A BRIEF LOOK AT THE KURDS IN AZERBAIJAN

After a Byzantine passage through language, phone calls, and meetings, one evening I finally found myself in a small living room in one many worn-concrete Soviet era apartment buildings in Baku, Azerbaijan. I was in the country for a 3-week visit which was to include searching out the story of the Kurds in this ex-Soviet republic as I had been doing throughout the region over the past decade.

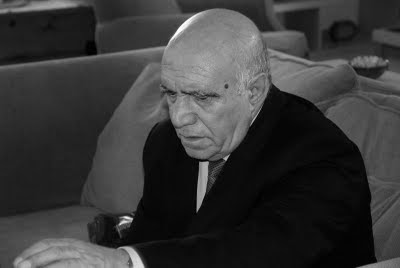

Ahmede Hepo

“In 1926 my parents moved from Igdir, Turkey to Arashdt, Armenia where I was born in 1934,” Ahmede Hepo began, pleased with my persistent interest in hearing his story.

Ahmede Hepo's Parents

We found the towns with which I was familiar, merely a thumb's width apart on my crease-torn map and 50 kilometers on the ground. Both enjoy unparalleled views of epic Mount Ararat. When Ahmede's parents made the short journey the ink had barely dried on the 1924 Lausanne Treaty map that finally defined the post-World War I nation-state boundaries carving-up the defunct Ottoman Empire; on the ground the lines had barely existed to those living in the region.

Ahmede Hepo, a 77-year old Azeri Kurd, is a short squarish man balder than I. He wears the gravitas of an educated man as comfortably as he wears his suit and tie.

Ahmede Hepo

“It was in 1937 that Stalin ordered the relocation of 50,000 Muslim Kurds from Arashadt to Kazakastan and Kyrgystan in Central Asia. The Yezidi Kurds were allowed to stay. [Note: Yezidism is an ancient monotheistic non-Islamic religion that is practiced by around a half million Kurds.] My family was among the 10,000 that went to Kyrgystan.” He sat back in the soft sofa watching me intently as his 18-year old grandson translated from Azeri to English. Ahmede's daughter brought out tea and a cascade of cookies and candies.

This forced relocation was only one of many systematically and brutally imposed on ethnic groups in the Soviet Union by Stalin, beginning in 1937 and continuing to one degree or another through his death in 1953.

“I only spoke Kurdish [Kurmanji, the dominant dialect] so I never went to school in Kyrgystan. Ten years later Stalin ordered 5,000 of us to return to Arashadt. While we were gone many Armenians also returned and lived where we lived before. Of course they did not want us to stay. What were we to do?”

And so through the evening Ahmede shared his family's story with intent, patience and pride.

The Armenian Republic successfully petitioned Moscow to expell the Kurds, and once again they were sent packing to the east. This time it was to the Yevlax area in central Azerbaijan, where a significant Kurdish population remains to this day. After learning enough Azeri, a Turkic language, Ahmede went to school for the first time at the age of 15. In 1959 he returned to Armenia once again, this time to attend the Azeri Teachers College in Yerevan.

The the government-sanctioned Kurdish newspaper Reya Taze (The New Path) and Kurdish radio program were already established in Yerevan, and for the next 7 years Ahmede worked for both. It changed his life, for it was during this period he learned the written Kurmanji language, a love for which he carries to this day.

We cleared the low table for dinner – fried fish from the Caspian Sea, tomatoes and cucumbers heavily flecked with basil, and a basket of bread. To my delight Ahmede's daughter pulled up a stool and ate with us, me answering questions about other Kurdish communities I had visited over the years.

Dinner finished, Ahmede continued. In 1970 he moved his young family to Baku, the Azeri capital on the Caspian Sea, where he became the editor for Kurdish language publications. Twenty years later he authored his first “big book” on the “artistic nature” of the Kurds who left Turkey, and he continued writing in Kurdish through the years, now the author of ten books. Some of his books have been novels, and he translated an Azeri-authored novel on the the friendship between Azeris and Kurds. Ahmede gave me a copy of his most recent book, “The Most Decorated People” about notable Azeri Kurds.

In 1993, two years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the establishment of the the Republic of Azerbaijan, Ahmede began producing weekly programs for the state-owned radio station, which he continues to this day.

I would see Ahmede Hepo once more before leaving Azerbaijan.

Exiles and Immigrants

The estimate of the number of Kurds in Azerbaijan insanely ranges 12,000 to 200,000. The reasons include raw political manipulation, passive assimilation of a relocated minority ethnic group, and the unwillingness of many to self-identify as Kurds for fear of official and social discrimination. Regardless of the actual number, the Kurds constitute less than one percent of the country's population.

Azerbaijan, bordering on the oil-rich Caspian Sea, is the eastern-most of the three trans-Caucasus countries, the other two being Armenia and Georgia. It is on the periphery of what many accept as geographical Kurdistan, an irregularly shaped Texas-sized piece of real estate that disregards the national boundaries of Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. The movement of peoples – including Kurds – through the greater Middle East has been continuous through the millennia.

The first documented large immigration of Kurds into Azerbaijan was forced by the Persian Empire (Safavid Dynasty) in the 16th century to defend its northwestern frontier. During tsarist Russia's cat-and-mouse game of intrigue and skirmishes with the weakening Ottoman Empire in 18th and 19th centuries, Kurds, other ethnicities and religious adherents were carried by the winds of perceived security. Early in the Soviet era, Moscow established short-lived administrative region “Red Kurdistan” (1923-1929) which was squeezed between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Following the break-up of the Soviet Union, Azerbaijan and Armenia entered into the Nagorno-Karabakh War (1988-1994). As a result the Kurds and others of western Azerbaijan were once again relocated – this time becoming refugees within their own country. Many still live in relocation camps.

“We are all Azeris”

Over the next several weeks traveling throughout Azerbaijan I sought out opportunities to learn more about the Kurds. It was an amazing and consistent journey of acknowledgment and denial.

In these conversations, invariably the Azeri nationals would seamlessly shift to talk about the other two principal minorities in their country – the indigenous Lezgis in the northeast, and Talysh in the southeast along the Iranian border – wanting to bolster their country's credentials of tolerance. One of the unspoken differences between these minorities is that the Kurds have always been interlopers, and interlopers with a reputation to be mistrusted, if not feared.

And floating about were the rumors: The Kurds were the mafia in Baku; President Aliyev kept a personal guard of Kurds hidden away in the sprawling compound near Ganja; the Azeri Kurds were supporting the Turkish Kurd guerrilla movement, the PKK, and; some of the refugee Kurds from the Nagorno-Karabakh region were agents for Armenia.

“First I must learn English”

Ahmede and I met once again under the epic statue of Nariman Narimanov, an Azeri statesman-writer national hero of the early 20th century. He arrived with his grandson and rail-thin woman in her forties. We dodged the traffic and went to the nearby well-appointed modern apartment of ex-patriot friends. Shoes were shed at the door, tea was served, and Ahmede unpacked papers and photographs from his briefcase.

Ahmede Hepo with members of family in Yevlax

“These are my grandparents, and these my parents,” he said, “And here I am in Yevlax with some of my family.” Ahmede was a man clearly aware and proud of his roots, but somehow blinded to the what I and others believe to be the inevitable fate of assimilation of Kurds in Azerbaijan.

With Gulnara and Ahmede Hepo

Maps and books were once again arrayed on the table and floor, and the conversations were sucked into the geographic and numeric details of the Nagorno-Karabakh refugees in Azerbaijan. Inquiries as to the relationships between different groups of Kurds, the economic conditions of Kurds, and fate of the Kurdish language in Azerbaijan were all swept away with a figurative gesture as if to say, “My success and passion for Kurdishness is a testament to the future of Kurds in Azerbaijan.”

Gulnara, which means “fire flower” in Farsi, works for an international organization and is studying the psychology of minorities. Certainly, I thought, she would add insights. But as with everyone else, she dismissed the notion of minority problems in Azerbaijan, she and Ahmede echoing the same theme, and she citing the policies of the government. [Note: These are not empty boasts. International organizations routinely give the Azeri government passing-to-high marks for its treatment of ethnic minorities.] She did acknowledge, however, that the fewer and fewer Kurds were speaking Kurmanji; that once removed from their “homelands” they were much more prone to learn Azeri to better their chances for an improved social and economic conditions. Ahmede nodded, straightening his pale blue tie.

We unfolded ourselves from the soft chairs and sofas and began the long ceremony of goodbyes. Yusef helped his grandfather with his coat, and I the same for Gulnara.

When leaving, I asked Yusef if he intended to learn Kurmanji, for he spoke none. “Yes, but first I must learn to speak English better.”

Postscript

Azerbaijan's Kurds Fear Loss Of National Identity

July 2, 2011

BAKU, Azerbaijan, — Representatives of Azerbaijan's Kurdish minority convened a press conference in Baku on June 29 to highlight perceived threats to their continued survival as a separate ethnic group.

Tahir Suleymanov, editor of the newspaper "Diplomat," read out an appeal on behalf of the Kurds to Azerbaijan's President Ilham Aliyev. The appeal stressed that like any other ethnic group, the Kurds need schools with Kurdish as the language of instruction, theatres, and TV programs in their native language, in order to preserve their national identity.

It also noted that Azerbaijani Kurds consider it prudent to conceal their ethnic identity, as publicly identifying oneself as a Kurd "can elicit a negative reaction."

Russian media reports on the press conference do not specify why or whether those present elaborated on that claim.

Suleymanov also made the point that not a single one of the 125 members of the Azerbaijani parliament is Kurdish.

source: http://www.ekurd.net

After a Byzantine passage through language, phone calls, and meetings, one evening I finally found myself in a small living room in one many worn-concrete Soviet era apartment buildings in Baku, Azerbaijan. I was in the country for a 3-week visit which was to include searching out the story of the Kurds in this ex-Soviet republic as I had been doing throughout the region over the past decade.

Ahmede Hepo

“In 1926 my parents moved from Igdir, Turkey to Arashdt, Armenia where I was born in 1934,” Ahmede Hepo began, pleased with my persistent interest in hearing his story.

Ahmede Hepo's Parents

We found the towns with which I was familiar, merely a thumb's width apart on my crease-torn map and 50 kilometers on the ground. Both enjoy unparalleled views of epic Mount Ararat. When Ahmede's parents made the short journey the ink had barely dried on the 1924 Lausanne Treaty map that finally defined the post-World War I nation-state boundaries carving-up the defunct Ottoman Empire; on the ground the lines had barely existed to those living in the region.

Ahmede Hepo, a 77-year old Azeri Kurd, is a short squarish man balder than I. He wears the gravitas of an educated man as comfortably as he wears his suit and tie.

Ahmede Hepo

“It was in 1937 that Stalin ordered the relocation of 50,000 Muslim Kurds from Arashadt to Kazakastan and Kyrgystan in Central Asia. The Yezidi Kurds were allowed to stay. [Note: Yezidism is an ancient monotheistic non-Islamic religion that is practiced by around a half million Kurds.] My family was among the 10,000 that went to Kyrgystan.” He sat back in the soft sofa watching me intently as his 18-year old grandson translated from Azeri to English. Ahmede's daughter brought out tea and a cascade of cookies and candies.

This forced relocation was only one of many systematically and brutally imposed on ethnic groups in the Soviet Union by Stalin, beginning in 1937 and continuing to one degree or another through his death in 1953.

“I only spoke Kurdish [Kurmanji, the dominant dialect] so I never went to school in Kyrgystan. Ten years later Stalin ordered 5,000 of us to return to Arashadt. While we were gone many Armenians also returned and lived where we lived before. Of course they did not want us to stay. What were we to do?”

And so through the evening Ahmede shared his family's story with intent, patience and pride.

The Armenian Republic successfully petitioned Moscow to expell the Kurds, and once again they were sent packing to the east. This time it was to the Yevlax area in central Azerbaijan, where a significant Kurdish population remains to this day. After learning enough Azeri, a Turkic language, Ahmede went to school for the first time at the age of 15. In 1959 he returned to Armenia once again, this time to attend the Azeri Teachers College in Yerevan.

The the government-sanctioned Kurdish newspaper Reya Taze (The New Path) and Kurdish radio program were already established in Yerevan, and for the next 7 years Ahmede worked for both. It changed his life, for it was during this period he learned the written Kurmanji language, a love for which he carries to this day.

We cleared the low table for dinner – fried fish from the Caspian Sea, tomatoes and cucumbers heavily flecked with basil, and a basket of bread. To my delight Ahmede's daughter pulled up a stool and ate with us, me answering questions about other Kurdish communities I had visited over the years.

Dinner finished, Ahmede continued. In 1970 he moved his young family to Baku, the Azeri capital on the Caspian Sea, where he became the editor for Kurdish language publications. Twenty years later he authored his first “big book” on the “artistic nature” of the Kurds who left Turkey, and he continued writing in Kurdish through the years, now the author of ten books. Some of his books have been novels, and he translated an Azeri-authored novel on the the friendship between Azeris and Kurds. Ahmede gave me a copy of his most recent book, “The Most Decorated People” about notable Azeri Kurds.

In 1993, two years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the establishment of the the Republic of Azerbaijan, Ahmede began producing weekly programs for the state-owned radio station, which he continues to this day.

I would see Ahmede Hepo once more before leaving Azerbaijan.

Exiles and Immigrants

The estimate of the number of Kurds in Azerbaijan insanely ranges 12,000 to 200,000. The reasons include raw political manipulation, passive assimilation of a relocated minority ethnic group, and the unwillingness of many to self-identify as Kurds for fear of official and social discrimination. Regardless of the actual number, the Kurds constitute less than one percent of the country's population.

Azerbaijan, bordering on the oil-rich Caspian Sea, is the eastern-most of the three trans-Caucasus countries, the other two being Armenia and Georgia. It is on the periphery of what many accept as geographical Kurdistan, an irregularly shaped Texas-sized piece of real estate that disregards the national boundaries of Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. The movement of peoples – including Kurds – through the greater Middle East has been continuous through the millennia.

The first documented large immigration of Kurds into Azerbaijan was forced by the Persian Empire (Safavid Dynasty) in the 16th century to defend its northwestern frontier. During tsarist Russia's cat-and-mouse game of intrigue and skirmishes with the weakening Ottoman Empire in 18th and 19th centuries, Kurds, other ethnicities and religious adherents were carried by the winds of perceived security. Early in the Soviet era, Moscow established short-lived administrative region “Red Kurdistan” (1923-1929) which was squeezed between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Following the break-up of the Soviet Union, Azerbaijan and Armenia entered into the Nagorno-Karabakh War (1988-1994). As a result the Kurds and others of western Azerbaijan were once again relocated – this time becoming refugees within their own country. Many still live in relocation camps.

“We are all Azeris”

Over the next several weeks traveling throughout Azerbaijan I sought out opportunities to learn more about the Kurds. It was an amazing and consistent journey of acknowledgment and denial.

“Yes, of course there are Kurds in Azerbaijan, but it does not matter – we are all Azeris.”

“My family is very close friends with some Kurdish families, but no, it would not be possible to meet them.”

“There is no problem in visiting the 'relocation camp' but we should not go there; the officials will ask too many questions.”

In these conversations, invariably the Azeri nationals would seamlessly shift to talk about the other two principal minorities in their country – the indigenous Lezgis in the northeast, and Talysh in the southeast along the Iranian border – wanting to bolster their country's credentials of tolerance. One of the unspoken differences between these minorities is that the Kurds have always been interlopers, and interlopers with a reputation to be mistrusted, if not feared.

And floating about were the rumors: The Kurds were the mafia in Baku; President Aliyev kept a personal guard of Kurds hidden away in the sprawling compound near Ganja; the Azeri Kurds were supporting the Turkish Kurd guerrilla movement, the PKK, and; some of the refugee Kurds from the Nagorno-Karabakh region were agents for Armenia.

“First I must learn English”

Ahmede and I met once again under the epic statue of Nariman Narimanov, an Azeri statesman-writer national hero of the early 20th century. He arrived with his grandson and rail-thin woman in her forties. We dodged the traffic and went to the nearby well-appointed modern apartment of ex-patriot friends. Shoes were shed at the door, tea was served, and Ahmede unpacked papers and photographs from his briefcase.

Ahmede Hepo with members of family in Yevlax

“These are my grandparents, and these my parents,” he said, “And here I am in Yevlax with some of my family.” Ahmede was a man clearly aware and proud of his roots, but somehow blinded to the what I and others believe to be the inevitable fate of assimilation of Kurds in Azerbaijan.

With Gulnara and Ahmede Hepo

Maps and books were once again arrayed on the table and floor, and the conversations were sucked into the geographic and numeric details of the Nagorno-Karabakh refugees in Azerbaijan. Inquiries as to the relationships between different groups of Kurds, the economic conditions of Kurds, and fate of the Kurdish language in Azerbaijan were all swept away with a figurative gesture as if to say, “My success and passion for Kurdishness is a testament to the future of Kurds in Azerbaijan.”

Gulnara, which means “fire flower” in Farsi, works for an international organization and is studying the psychology of minorities. Certainly, I thought, she would add insights. But as with everyone else, she dismissed the notion of minority problems in Azerbaijan, she and Ahmede echoing the same theme, and she citing the policies of the government. [Note: These are not empty boasts. International organizations routinely give the Azeri government passing-to-high marks for its treatment of ethnic minorities.] She did acknowledge, however, that the fewer and fewer Kurds were speaking Kurmanji; that once removed from their “homelands” they were much more prone to learn Azeri to better their chances for an improved social and economic conditions. Ahmede nodded, straightening his pale blue tie.

We unfolded ourselves from the soft chairs and sofas and began the long ceremony of goodbyes. Yusef helped his grandfather with his coat, and I the same for Gulnara.

When leaving, I asked Yusef if he intended to learn Kurmanji, for he spoke none. “Yes, but first I must learn to speak English better.”

Postscript

Azerbaijan's Kurds Fear Loss Of National Identity

July 2, 2011

BAKU, Azerbaijan, — Representatives of Azerbaijan's Kurdish minority convened a press conference in Baku on June 29 to highlight perceived threats to their continued survival as a separate ethnic group.

Tahir Suleymanov, editor of the newspaper "Diplomat," read out an appeal on behalf of the Kurds to Azerbaijan's President Ilham Aliyev. The appeal stressed that like any other ethnic group, the Kurds need schools with Kurdish as the language of instruction, theatres, and TV programs in their native language, in order to preserve their national identity.

It also noted that Azerbaijani Kurds consider it prudent to conceal their ethnic identity, as publicly identifying oneself as a Kurd "can elicit a negative reaction."

Russian media reports on the press conference do not specify why or whether those present elaborated on that claim.

Suleymanov also made the point that not a single one of the 125 members of the Azerbaijani parliament is Kurdish.

source: http://www.ekurd.net